Week 9: Finding Your Voice

Nine mechanical components of narrative voice, so you can dial in your own voice with a satisfying click.

Some call it style. Some call it tone. It answers the question: What is the writing like to read? Concise and minimalist. Playfully excessive. Sardonic and emotional. This week I’ve been working on reading my novel aloud, and figuring out how I want it to sound. Tone is part of it, but that’s too specific. Style is part of it, but that’s too broad. Style, tone, voice — these are all just vocabulary words, and beyond a literature class exam, they’re only important if they’re useful. The word I prefer, when talking about how the writing sounds, and how it feels to read, is not style or tone but voice.

When I read fiction, there’s always someone talking to me. Even the most remote, invisible narrator is speaking into their present moment. That “speaking” is the fiction’s voice. Descriptive words for this can be hard to pin down. Rather than surrendering to the subjectivity of voice, as if it’s a mystical quality like porn or art that you have to sense instead of map, I’m going to map it for us, into nine distinct elements. Is this a little too much “how the sausage is made” content? Well, if you’re making sausage (and we are!), you want to make it deliberately. Learning to control these dials, and understand how your prose is constructed, can help you distinguish one narrator from another, and fine tune the way your novel is read.

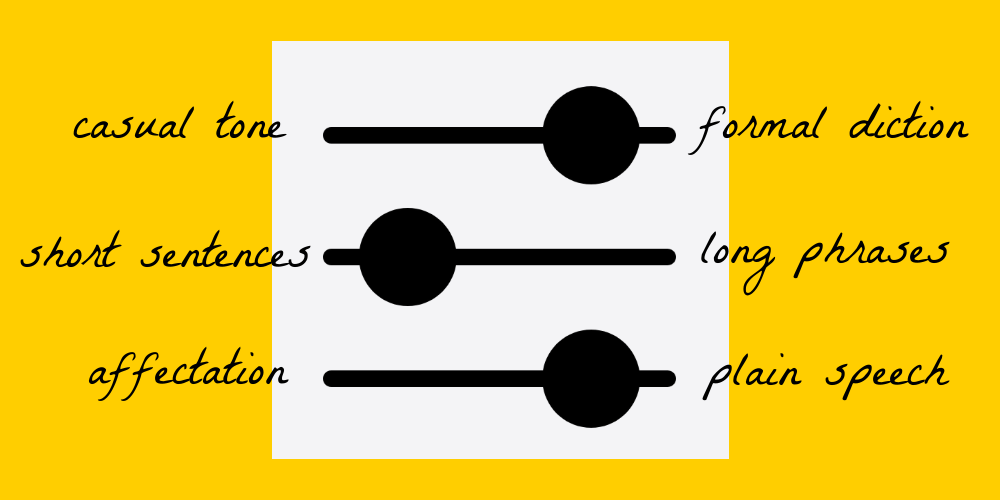

Imagine a set of sliders, like faders on a music producer’s mixing board. Each defines a spectrum between extremes, and is infinitely specific in its measurement. Figuring out exactly where your narrator falls in these ranges can help you keep your voice consistent across not just chapter one but a whole novel, can help you distinguish multiple narrators from each other, and can set you off hunting that illusive beast, your unique authorial style. It can help you understand what you are already doing intuitively, so you can control it.

Nine Metrics for Defining Your Voice

Here are the elements these sliders define:

Formal diction ←→ Casual diction

Diction means the words and phrases the speaker uses, from carefully chosen academic terms to chatty y’alls and yeahs. Settle on a character’s lexile, and then decide, within that ability, what level they choose to use to communicate. Will the prose sound deliberately constructed, or off the cuff?Abrasive ←→ Inviting

Some narrators don’t care what the reader thinks, and some are ingratiating to the point of sounding nervous. Your narrator’s attitude toward the reader, toward whether or not they will be heard or believed, is something that can vary with the subject matter at hand, or can develop over the course of the novel. Narrators might demonstrate this with emotional appeals, or excessive description, and sometimes openly hostile, defensive rants.Dense structure ← → Loose structure

When you look at your fiction on the page, are there big fat paragraphs that fill dense rectangles, or are there lots of single line paragraphs, leaving white space and controlling pauses? Varying the structure intentionally can control the pace at which your reader consumes the text, as well as the urgency of the voice.Figures of speech ← → Plain speech

If you have alternating narrators, one of the easiest ways to help your reader identify which character is speaking without looking at the name at the front of the chapter is to give a character a set of idioms or theme for their figures of speech. Perhaps one character uses nautical metaphors and similes, or regional idioms, phrases from a particular language, or certain interjections. You can also create a character who speaks very literally, and rarely uses similes. Then when they do, it stands out.Sight ← → Sound

When a narrator describes a scene, how much are they relying on visuals like color, movement, and physical spaces, and how much are they including sounds, smells, and other senses. If you have one narrator whose voice is characterized by including sounds or smells from the environment, and another that notices color, that will help the reader distinguish them, even if unconsciously.Short sentences ← → Long phrases

Voice is linked to point-of-view, with proximity and distance in place and time. Shorter sentences give a sense of immediacy and urgency, while longer phrases distance the narrator, subdue the pace. In expository writing classes we’re taught to vary the length of our sentences, and this is good advice! Maybe this slider is right in the middle. But in developing a narrator’s voice, you may push to stick with longer sentences or shorter fragments, overall.Explaining ← → Assuming

Some narrators will not miss a chance to halt and provide info and background to the reader, and some will charge forward relentlessly, tossing the reader into the deep end of the story without a raft. An explaining narrator might be found using a lot of parentheticals to contain their qualifiers and explanations, or even take whole paragraphs for digressions and details. An assuming narrator will use proper nouns without stopping to identify them, local vocabulary without defining it. Explainers use lists and classifications. Assumers skip flashbacks.Literary ← → Utilitarian

Creating alliteration, playing with internal rhymes, using lines with a specific rhythm or meter, repeating words or phrases — these are characteristics of literary language. Constructing lyrical prose can give the voice a sense of playfulness, or make the reader feel the narrator is reaching for beauty in their language. Or persuasiveness. On the other hand, a narrator could deliver minimalist prose with so such flapping and fluttering.Quirky ← → Normal

When I say quirky, I’m referring not to literary devices, but to some mechanical feature that sets this narrator apart. Like using a lot of em dashes, or a catchphrase, or stream of consciousness, or dialect. Even if you have a third person narrator telling all your stories, and that narrator is very close, in your mind, to you yourself, they can still have a unique way of phrasing things, so that when a reader opens your book, they know immediately who they’re reading.

My Progress

Starting over last week was fantastic, and I haven’t stopped cackling with glee over just reaching into my novel’s innards and ripping that mess right up. I’ve still been limiting my word count to what would be around 50 words a day, and I’m past 2000 words now, so I’m really thinking now about what kind of voice I want my story to have.

I tend to slip into a kind of wry and academic tone. I tend to skip connective words like “so that” and use too many semicolons. I like to juxtapose heavy vocabulary with short, simple phrases. I end questions with periods. These are things I know about the mechanics of my writing, and some of this knowledge only came from having my novels professionally copy-edited by my publisher.

If you’ve not been thinking carefully about this stuff yet, cast an eye over what you have so far and see where your sliders are. Even if you’re determined that voice is something that must be felt and not analyzed, you should still know your own writing, and look back objectively at what you’ve got. Maybe these metrics will help you understand mechanically what you’ve created intuitively. I hope so! Next week, we’re on to finishing up chapter 1.

If you like this numerical approach to writing a novel, please share this post, and refer new subscribers with the referral button. If you refer someone to subscribe to this Substack, you’ll probably find that tote bag full of power tools you are missing.

I love the way you unpacked this. The slider is a great visual!

Beautiful

Please take a look at mine on creation of art and non duality

https://substack.com/@collapseofthewavefunction/note/p-167021101?r=5tpv59&utm_medium=ios&utm_source=notes-share-action